www.industryemea.com

12

'25

Written on Modified on

Producing chemical feedstocks using concentrated solar energy

As part of the EU-funded FlowPhotoChem project, DLR, in collaboration with industry and research contributors, has set up and tested a new demonstration plant.

www.dlr.de

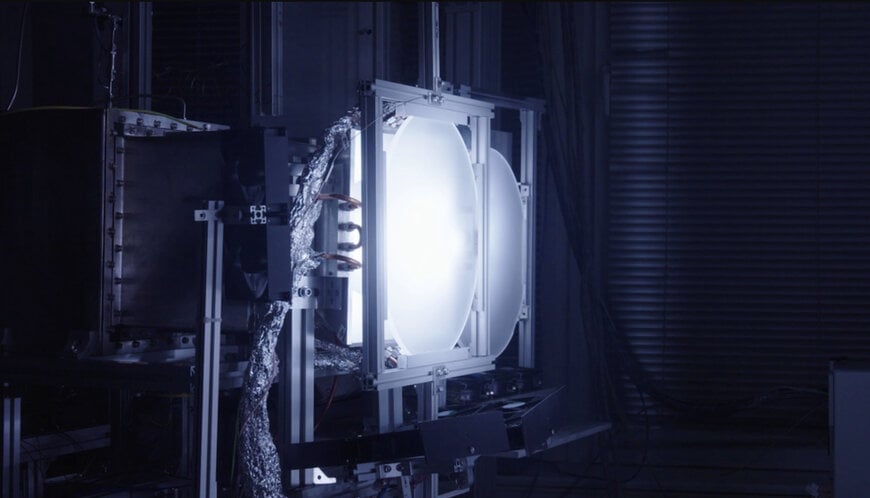

Irradiation of the FlowPhotoChem reactors: In this multi-stage experimental setup, the first and second reactors use concentrated solar radiation to produce the basic materials hydrogen and carbon monoxide from water and carbon dioxide. Ethylene – the target product – is then produced in the third reactor. Credit: © DLR. All rights reserved

Many chemical feedstocks (raw materials that are processed into chemicals, fuels and other products) such as ethylene, propylene, methanol and ammonia, are derived from crude oil and natural gas. These substances are essential for many industries, including plastics manufacturing, fuel production and fertiliser synthesis. However, the processes used to produce them consumes vast amounts of raw materials and energy, and, in Germany alone, releases nearly 40 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents annually. As part of the EU's FlowPhotoChem project, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) has set up and tested a demonstration plant that successfully shows that feedstocks can be produced in a more climate-compatible manner in the future.

Working alongside European research institutes and companies, DLR has tested a process in which concentrated solar radiation supplies a significant portion of the energy required to produce chemical feedstocks from water and carbon dioxide. This concentrated solar radiation can be intensified to several hundred times the strength of normal sunlight. "Research into the solar production of chemical feedstocks enables us to develop fully renewable processes for the large-scale production of these chemicals and energy carriers in the future," explains Michael Wullenkord from the DLR Institute of Future Fuels, who led DLR's contribution to the project. Solar-driven processes could play a crucial role in reducing the industry's carbon footprint and reliance on fossil fuel resources. The primary focus of the FlowPhotoChem project has been the production of ethylene, a key precursor to polyethylene (PE). This plastic is predominantly used in films and packaging and is the most widely used plastic worldwide in terms of volume.

Three-stage process converts readily available raw materials into highly sought-after chemical feedstocks

At its core, the demonstration plant is composed of three interconnected modules, developed by project contributors. These specialised 'reactors' facilitate different chemical processes that convert the starting materials – water and carbon dioxide – into the target product, ethylene.

In the first reactor, water molecules are split into hydrogen and oxygen using energy from concentrated solar radiation. The hydrogen produced is then fed into the second reactor module where it is combined with carbon dioxide – either captured from the air or sourced from industrial emissions. Here, concentrated solar radiation is once again employed, this time to produce carbon monoxide. In the third and final stage, the carbon monoxide is converted into ethylene or other target chemical products using electrical energy, preferably supplied by photovoltaic systems.

The FlowPhotoChem experimental setup: In collaboration with international collaborators from research and industry, DLR developed the system’s components over a period of four years. These were then assembled and tested together during the final series of experiments using DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne. Credit: © DLR. All rights reserved

Setup and testing in DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne

The DLR Institute of Future Fuels, with sites in Jülich and Cologne, was responsible for designing, constructing and testing a fully operational system for the FlowPhotoChem project. "The main sticking points were the combination of the three reactors and their integration into the overall system," explains DLR scientist Michael Wullenkord. To achieve this, the institute also developed models of the complete system to optimise efficiency and coordination between all components later on. Each reactor module was provided by a specialised project participant. The first reactor was developed by SoHHytec, a spin-off from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL). The Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV) built the second reactor, and the third was developed by the Hungarian company eChemicles, with support from the University of Szeged (SZTE).

The complete system was assembled and commissioned at DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne, where xenon lamps supplied the concentrated – albeit artificial – solar radiation required to operate the first and second reactors. This controlled environment allowed experiments to proceed independently of weather conditions. The project also benefited from DLR's extensive experience in handling complex experimental setups, including with comprehensive measurement and control technologies. One of the many challenges was to precisely fine-tune the alignment and intensity of the radiation to optimise its impact on the reactor surfaces.

The assembled demonstration plant occupies an entire test hall, making it significantly larger than typical laboratory-scale systems. During a one-week test phase at DLR, the FlowPhotoChem team successfully demonstrated the operation of the integrated system and gained valuable insights for future refinements. In addition, the team further enhanced pre-existing models and identified potential areas for improvement. "By further optimising reactor modules, improving operational strategies and implementing advanced heat and power management – for example, by utilising waste heat or surplus electricity for the overall process – the system could ultimately achieve exceptionally high levels of efficiency," explains Wullenkord.

Since the use of these technologies relies on sufficient direct solar radiation, they are best suited for regions in the global ‘sun belt’. This includes southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece in particular, but also Australia, the United States, and regions of North Africa and the Middle East.

Many chemical feedstocks (raw materials that are processed into chemicals, fuels and other products) such as ethylene, propylene, methanol and ammonia, are derived from crude oil and natural gas. These substances are essential for many industries, including plastics manufacturing, fuel production and fertiliser synthesis. However, the processes used to produce them consumes vast amounts of raw materials and energy, and, in Germany alone, releases nearly 40 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents annually. As part of the EU's FlowPhotoChem project, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) has set up and tested a demonstration plant that successfully shows that feedstocks can be produced in a more climate-compatible manner in the future.

Working alongside European research institutes and companies, DLR has tested a process in which concentrated solar radiation supplies a significant portion of the energy required to produce chemical feedstocks from water and carbon dioxide. This concentrated solar radiation can be intensified to several hundred times the strength of normal sunlight. "Research into the solar production of chemical feedstocks enables us to develop fully renewable processes for the large-scale production of these chemicals and energy carriers in the future," explains Michael Wullenkord from the DLR Institute of Future Fuels, who led DLR's contribution to the project. Solar-driven processes could play a crucial role in reducing the industry's carbon footprint and reliance on fossil fuel resources. The primary focus of the FlowPhotoChem project has been the production of ethylene, a key precursor to polyethylene (PE). This plastic is predominantly used in films and packaging and is the most widely used plastic worldwide in terms of volume.

Three-stage process converts readily available raw materials into highly sought-after chemical feedstocks

At its core, the demonstration plant is composed of three interconnected modules, developed by project contributors. These specialised 'reactors' facilitate different chemical processes that convert the starting materials – water and carbon dioxide – into the target product, ethylene.

In the first reactor, water molecules are split into hydrogen and oxygen using energy from concentrated solar radiation. The hydrogen produced is then fed into the second reactor module where it is combined with carbon dioxide – either captured from the air or sourced from industrial emissions. Here, concentrated solar radiation is once again employed, this time to produce carbon monoxide. In the third and final stage, the carbon monoxide is converted into ethylene or other target chemical products using electrical energy, preferably supplied by photovoltaic systems.

The FlowPhotoChem experimental setup: In collaboration with international collaborators from research and industry, DLR developed the system’s components over a period of four years. These were then assembled and tested together during the final series of experiments using DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne. Credit: © DLR. All rights reserved

Setup and testing in DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne

The DLR Institute of Future Fuels, with sites in Jülich and Cologne, was responsible for designing, constructing and testing a fully operational system for the FlowPhotoChem project. "The main sticking points were the combination of the three reactors and their integration into the overall system," explains DLR scientist Michael Wullenkord. To achieve this, the institute also developed models of the complete system to optimise efficiency and coordination between all components later on. Each reactor module was provided by a specialised project participant. The first reactor was developed by SoHHytec, a spin-off from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL). The Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV) built the second reactor, and the third was developed by the Hungarian company eChemicles, with support from the University of Szeged (SZTE).

The complete system was assembled and commissioned at DLR's High-Flux Solar Simulator in Cologne, where xenon lamps supplied the concentrated – albeit artificial – solar radiation required to operate the first and second reactors. This controlled environment allowed experiments to proceed independently of weather conditions. The project also benefited from DLR's extensive experience in handling complex experimental setups, including with comprehensive measurement and control technologies. One of the many challenges was to precisely fine-tune the alignment and intensity of the radiation to optimise its impact on the reactor surfaces.

The assembled demonstration plant occupies an entire test hall, making it significantly larger than typical laboratory-scale systems. During a one-week test phase at DLR, the FlowPhotoChem team successfully demonstrated the operation of the integrated system and gained valuable insights for future refinements. In addition, the team further enhanced pre-existing models and identified potential areas for improvement. "By further optimising reactor modules, improving operational strategies and implementing advanced heat and power management – for example, by utilising waste heat or surplus electricity for the overall process – the system could ultimately achieve exceptionally high levels of efficiency," explains Wullenkord.

Since the use of these technologies relies on sufficient direct solar radiation, they are best suited for regions in the global ‘sun belt’. This includes southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece in particular, but also Australia, the United States, and regions of North Africa and the Middle East.

www.dlr.de